The Stones moved to France in 1971, and recorded Exile on Main Street, presenting themselves as victims of the anti-narcotics police and the British treasury, which at that time had 83% of the billionaire income.

Keith Richards recalls the fiscal exile in his autobiography Life as if moving to the Chateau de Nellcote in Nice (where the album was recorded), with a view of his new yacht Mandrax, moored in the bay of Villefranche, was a blow against the empire British. “The power never expected us to leave; they did not understand that we would become stronger, that they would inspire us to do Exile on Main Street, perhaps the best thing we have ever done.”

That is why it is even more shocking to see that only three years before, during the 1968 protests, Jagger was a true street rebel coordinating his presence in demonstrations with that of Trotskyist leaders like Tariq Ali, who not only demanded that the “upper bourgeoisie” pay taxes but intended to expropriate their assets. Ali remembers it in his conversation with La Vanguardia. Following the Tet offensive in the Vietnam War in early ’68, a protest movement grew rapidly and, when thousands of protesters fought a pitched battle against mounted riot police, in London’s Grosvenor Square, there, among the protesters, there was Mick Jagger.

“Jagger was pretty committed back then; he had more credibility than the Beatles,” says Ali. After the violent crushing of the protest, Jagger showed his weakness for the big stage productions that would soon be seen in the mega shows of the Stones’ tours. “Right there (in Grosvenor Square) I thought: If they want to use horses, we are going to have 10,000 people riding horses!” He said in an interview in the counterculture magazine International Times.

Disappointed by the docility of the British people, Jagger wrote Street fighting man after his experience in Grosvenor Square. “He wrote us the letter on a paper to be published in Black Dwarf (Black Dwarf, the revolutionary newspaper that would later become Red Mole, Red Topo), and as soon as we took a photo of the paper, I threw it away; because in that So we had no interest in celebrities beyond their political commitment.”

But while the Trotskyists and Maoists of ’68 rejected the rock star cult, they did understand the influence exerted by figures like Jagger and John Lennon.

When in 1967, The Beatles (with the presence of Jagger) broadcast All You Need Is Love live, they reached more than 300 million people. Street fighting man could do the same in the next revolutionary phase:

“Summer has come and it is time to fight in the streets,” Jagger sings in London, scolding her for being a “sleeping city.” Jagger, who had studied at the London School of Economics, now the headquarters for student protests under the leadership of Trotskyist Robin Blackburn, concluded in an interview with the International Times: “The system is rotten (…) The time has come The revolution is valid.”

Jagger’s presence at the Grosvenor Square rally contrasted with the absence of the Beatles. John Lennon – theoretically the rock star with the best revolutionary credentials – had caused brutal disenchantment on the left by recording the ambivalent Revolution in the same year. “You say you want a revolution (..) But when you talk about destruction well, don’t count on me (or yes)”.

“The Beatles really disappointed us,” says Ali. John Hoyland of Black Dwarf even wrote an indignant letter to Lennon in October 1968: “There is no such thing as an educated revolution,” he wrote to the Beatle. “Lately, your music has lost its punch and the Stones are louder.” And Lennon responded by defending his lack of definition regarding the violent struggle in another letter to the same newspaper. “In the end, Lennon would prove much more assertive in his commitment to the Vietnam War than Jagger,” says Ali.

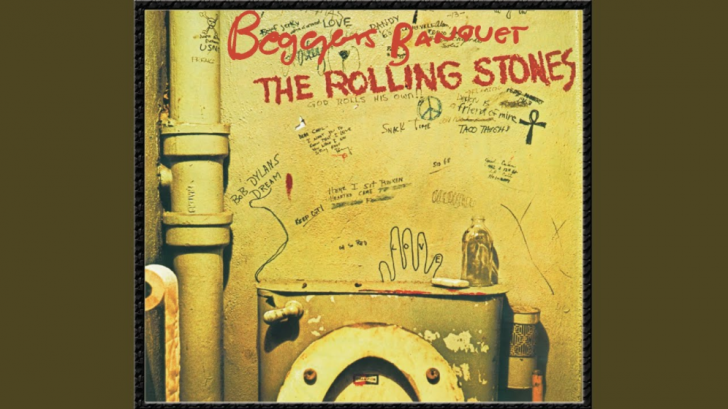

But in ’68, Jagger was the icon of the revolution and not Lennon. Even the French nouvelle vague Marxist filmmaker Jean Luc Godard, whose film Le Chinois about young Maoists in Paris was a precursor to May ’68, decided to shoot One plus one in the middle of that year, at the Olympic studios in London, where the Stones recorded the album Beggars Banquet and, specifically, the famous song Sympathy for the devil.

Goddard compared the evolution of that song in the studio – from Dylanesque folk of its first versions to a powerful and menacing samba – with the revolutionary process of a group of black panthers debating in a car junkyard. But in all the praise that the revolutionary left gave Jagger, it went unnoticed that Sympathy’s lyrics – based on a novel by the anti-Bolshevik Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov – included a rejection of the Russian revolution. ..) and killed the tsar and his ministers; Anastasia wept in vain “.

That is why, perhaps, a quarter of a century later it was selected as one of the ten best conservative songs by the right-wing National Review in Washington. And indeed, little by little, it became clearer that Jagger’s only protest was directed at Harold Wilson’s taxes. And that his only project was to turn the Rolling Stones into a lucrative multinational company worthy of representation at the Davos summit. Already in the early eighties, he declared himself a sympathizer not only of the devil but also of Margaret Thatcher.