When Hugh Syme discovered the name of Rush’s 10th studio record, 1984’s “Grace Under Pressure,” he quickly interpreted those subjects into colors.

The easy opening tip eventually produced one of the artist’s most notable paintings, which turned from his trademark photo-composite craft.

Having dinner and downing brandy at the Toronto home of drummer-lyricist Neil Peart in October 1983, Syme shot off a mild visual idea that developed on his tasteful of “continuing minimalism.”

“I really love the simplicity of albums like Discipline by King Crimson,” the prog-rock trio’s art director tells UCR. “[And] the early suggestions were influenced by my then admiration and study of pianist Keith Jarrett and an appreciation of those beautifully minimal jazz album covers from his ECM record releases with Manfred Eicher from Munich. I suggested I do a painting (in the minimal style of Mark Rothko) where we bisect the page.”

“When I heard about [the title], I said, ‘Why don’t we have ‘grace’ as a relaxing cream tone under the ‘pressure’ of the more ominous grey?'” he continued. “It was literally just split in half — a little like No Line on the Horizon became for U2. It was going to be hugely graphic. We both thought, ‘That’s it!'”

Just as both “drank more and more glasses of [Peart’s] obscenely rare Armagnac after dinner,” Syme started drawing more “figurative” designs.

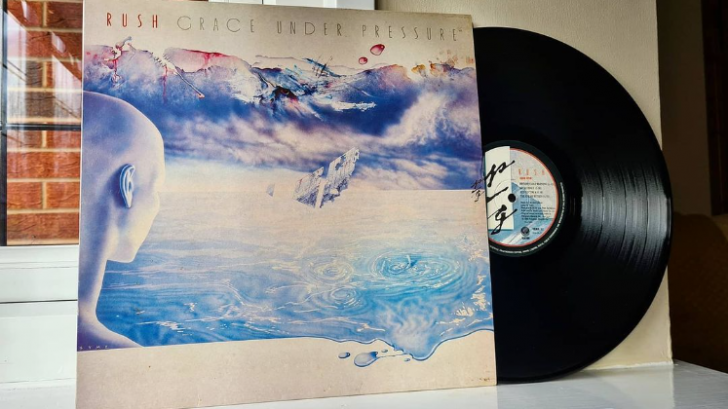

“We could have someone looking into a more elemental kind of sky — the pressure of weather and the grace of water,” the artist suggested, describing his concept for the stormy, slightly sci-fi-looking image. “It was all starting to sound right to Neil, and he said, ‘That sounds great too.’ It ended up being something I wanted to paint — and almost had to paint to pull off.”

Syme highlighted the characteristic duality with the “P/G fraction” lettering crammed on the right view of the painting. “I would render dozens of versions to create my signature ‘urgent’ calligraphic India ink letter forms that Geddy [Lee] once called a ‘murderous scrawl,'” he says. “And that would lay on my studio floor until the ink was dry.”

The creative director hasn’t designed for many record sleeves — though he did use that tool for the cover of their next album, 1985’s “Power Windows.”

“It also was one of the rare occasions [of painting for a cover],” he says, “even though I enjoy painting and continue to. It’s just not often enough because a lot of my technique delved more and more into the photo-composite realm of improbable reality.”