In 1983 one of the most outrageous lawsuits in the rock world took place: the Geffen record company sued a client of theirs, Neil Young, on the charge of being allegedly anti-commercial. Geffen asked for a compensation of 3 million dollars using as arguments in favor of the albums Trans and Everybody’s Rockin.

In the 70s Neil Young was one of the most successful artists of the moment with a very prolific career. In the early 1980s, David Geffen signed him to his record company thinking he had done one of the business of the century. What Geffen could not suspect is that the 80s would be the most erratic stage of Neil’s career, with jagged records and strange experiments. It was nothing new in fact, in the 70s after the success of Harvest Neil recorded the 3 most anti-commercial albums of that time and vetoed a fourth that had recorded that music was very similar to Harvest and could be a potential success in sales.

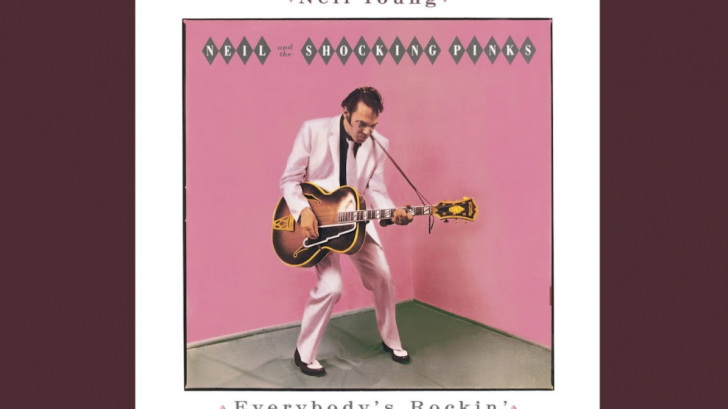

But in the 80s, Neil’s attitude was added to the fact that it was a very troublesome decade for all artists of the 70s. Neil experimented with electronic music, made a rockabilly album and a hard country album in a range of very few years. It was almost dizzying to continue his career. And of course, the records didn’t sell well.

“It was the first time in my life I’d been locked out of the studio by my record company,” Young said from the road while doing solo shows before the current Buffalo Springfield reunion tour.

“They thought I was all over the map and didn’t understand why I was out there playing country, although to me it sounded like B.B. King more than country,” he said. “To me it didn’t make any difference. They could call it whatever they wanted. But I’d already been making records a long time and I knew what I wanted to do. They could call it whatever they wanted.”

“They told me they wanted me to play rock ‘n’ roll, and told me I didn’t sound like Neil Young,” he said. “So I gave them ‘Everybody’s Rockin’ ’ and said, ‘This is a rock ‘n’ roll album by Neil Young after someone tells him what to do; this is exactly what you said you wanted.’ And we got way into it. I really liked it. As long as it’s good music and I’m playing with my friends, I don’t care what genre it is. All my music comes from all music — I’m not country, I’m not rock ‘n’ roll, I’m just me, and all these things are what I like.”

Unwilling to sacrifice his independence and artistic integrity to please his label, he eventually struck a deal with them that he would take a pay cut for his upcoming albums. This drove the country heavily Old Ways (1985), with guest appearances by Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings; tinted Landing On Water (1986); and the 1987 album Life, all of which met with mild success but fulfilled its final obligations to Geffen.

“The only musical person in the whole organization was the guy who owned it,” Young said. “He was going farther and farther down his own path; he was a media mogul and had other things on his mind…. None of the other people there were music people. They would send people out on the road, listen to the [Harvesters] band and go back to the record company and say I was not ready to record. They wouldn’t talk to me, then I’d hear they’d been there. They’d make suggestions on what they thought I ought to record. That’s not the way I work….”

“The record company did everything it could to stop me from doing what I did, but I look at it as some of the best work I ever did,” he said. “Up until that point I’d had a very supportive relationship with them.”

“Eventually they let me out of the contract,” he said. “They had to. They sued me, and I still didn’t stop.”

After almost a decade with Geffen, he went back to his former home at Reprise Records.

“I wish they were still here today, I would be doing more work with them,” Young said. “But so many important elements of the band are gone. It’s like playing ‘Harvest’ songs without Ben Keith — I just can’t go back there….”

“The only thing I can do is go forward,” he said. “It’s the only place that doesn’t have any ghosts and shadows from the past.”